Morality is not necessarily the product of religion, even though religions have contributed much to it. It is living amidst others that gives birth to the idea of right and wrong – and right and wrong have nothing to do with God but what is good for all the inhabitants during the invincible times as well as vulnerable times.

We appreciate the continuous efforts by Pew Research to update the public about changing social dynamics, it helps all of us understanding where we are going with it.

Courtesy – Pew Survey dated 10/5/17

Mike Ghouse

Center for Pluralism

Homosexuality, gender and religion

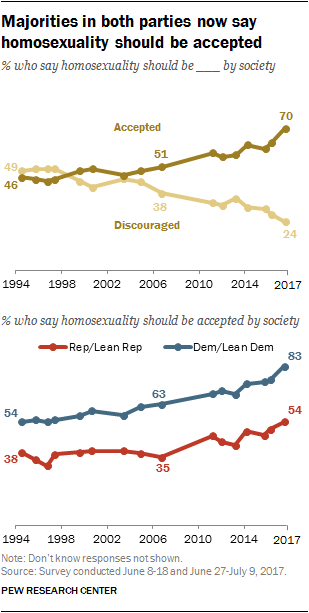

Over the past two decades, there has been a dramatic increase in public acceptance of homosexuality, as well as same-sex marriage. Still, the partisan divide on the acceptance of homosexuality has widened.

In views of challenges facing women, a majority of Americans say women continue to confront obstacles that make it more difficult for them to get ahead than men. Opinions about the obstacles facing women are divided along gender lines, but the partisan gap is wider than the gender gap.

Most Americans now say that it is not necessary to believe in God to be moral and have good values; this is the first time a majority has expressed this view in a measure dating back to 2002. While Republicans’ views have held steady over this period, an increasing share of Democrats say belief in God is not necessary in order to be a moral person.

Changing views on acceptance of homosexuality

Seven-in-ten now say homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared with just 24% who say it should be discouraged by society. The share saying homosexuality should be accepted by society is up 7 percentage points in the past year and up 19 points from 11 years ago.

Growing acceptance of homosexuality has paralleled an increase in public support for same-sex marriage. About six-in-ten Americans (62%) now say they favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. (For more on views of same-sex marriage, see: “Support for Same-Sex Marriage Grows, Even Among Groups That Had Been Skeptical,” released June 26, 2017.)

While there has been an increase in acceptance of homosexuality across all partisan and demographic groups, Democrats remain more likely than Republicans to say homosexuality should be accepted by society.

Overall, 83% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say homosexuality should be accepted by society, while only 13% say it should be discouraged. The share of Democrats who say homosexuality should be accepted by society is up 20 points since 2006 and up from 54% who held this view in 1994.

Among Republicans and Republican leaners, more say homosexuality should be accepted (54%) than discouraged (37%) by society. This is the first time a majority of Republicans have said homosexuality should be accepted by society in Pew Research Center surveys dating to 1994. Ten years ago, just 35% of Republicans held this view, little different than the 38% who said this in 1994.

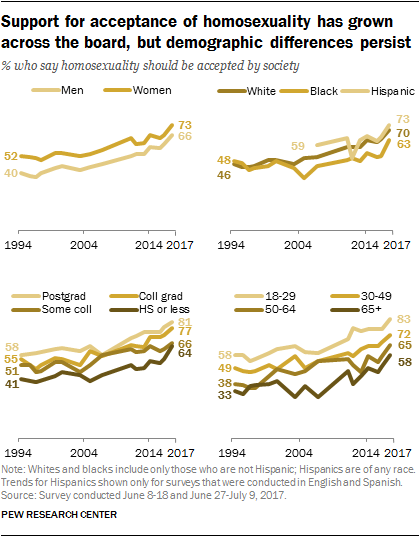

The growing acceptance of homosexuality has been broad-based, and majorities of most demographic groups now hold this view. However, differences remain across demographic groups in the size of the majority saying homosexuality should be accepted by society.

Age is strongly correlated with support for acceptance of homosexuality. Overall, 83% of those ages 18 to 29 say homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared with 72% of those ages 30 to 49, 65% of those 50 to 64, and 58% of those 65 and older.

Acceptance is greater among those with postgraduate (81%) and bachelor’s (77%) degrees than among those with some (69%) or no college experience (64%).

Do women continue to face obstacles to advancement?

Most Americans (55%) say that “there are still significant obstacles that make it harder for women to get ahead than men,” while 42% say “the obstacles that once made it harder for women than men to get ahead are now largely gone.”

Nearly two-thirds (64%) of women say there are still significant obstacles that make it harder for women to get ahead, while 34% say they are largely gone. By contrast, men are somewhat more likely to say obstacles to women’s progress are now largely gone (51%) than to say significant obstacles still exist (46%). The gender gap on this question is among the widest seen across the political values measured in this survey.

About seven-in-ten blacks (69%) think significant obstacles remain that make it harder for women to get ahead than men. This compares with 53% of whites and 52% of Hispanics.

Among both blacks and whites, the gender gap roughly mirrors that of the public overall. For example, 77% of black women and 60% of black men say significant barriers remain to women’s advancement (among whites, 62% of women and 43% of men say this). Among Hispanics, however, there is not a pronounced gender gap.

More postgraduates say significant obstacles to women’s progress still exist (70%) than say they are largely gone (28%). About six-in-ten college graduates (59%) also say women continue to face significant obstacles that men don’t. Views are more closely divided among those with some college experience and those with no more than a high school diploma.

There is a wide partisan gap in views of whether or not women continue to face greater challenges than men. By nearly three-to-one (73% vs. 25%), more Democrats and Democratic leaners say women continue to face significant obstacles that make it harder for them to get ahead than men. Republicans and Republican leaners take the opposite view: 63% say the obstacles that once made it harder for women to get ahead are now largely gone; fewer (34%) say significant obstacles still remain.

There is a wide partisan gap in views of whether or not women continue to face greater challenges than men. By nearly three-to-one (73% vs. 25%), more Democrats and Democratic leaners say women continue to face significant obstacles that make it harder for them to get ahead than men. Republicans and Republican leaners take the opposite view: 63% say the obstacles that once made it harder for women to get ahead are now largely gone; fewer (34%) say significant obstacles still remain.

Within both party coalitions, women are more likely than men to say significant obstacles to women’s progress still remain. Among Democrats, 79% of women say women still face significant obstacles, compared with 65% of men.

Among Republicans, a large majority of men (70%) say obstacles once faced by women are now largely gone. A smaller majority of Republican women (53%) share this view.

Views on religion, its role in policy

When it comes to religion and morality, most Americans (56%) say that belief in God is not necessary in order to be moral and have good values; 42% say it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.

When it comes to religion and morality, most Americans (56%) say that belief in God is not necessary in order to be moral and have good values; 42% say it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.

The share of the public that says belief in God is not morally necessary has edged higher over the past six years. In 2011, about as many said it was necessary to believe in God to be a moral person (48%) as said it was not (49%). This shift in attitudes has been accompanied by a rise in the share of Americans who do not identify with any organized religion.

Republicans are roughly divided over whether belief in God is necessary to be moral (50% say it is, 47% say it is not), little changed over the 15 years since the Center first asked the question. But the share of Democrats who say belief in God is not a condition for morality has increased over this period.

About two-thirds (64%) of Democrats and Democratic leaners say it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values, up from 51% who said this in 2011.

The growing partisan divide on this question parallels the widening partisan gap in religious affiliation.

About six-in-ten whites (62%) think belief in God is not necessary in order to be a moral person. By contrast, roughly six-in-ten blacks (63%) and 55% of Hispanics say believing in God is a necessary part of being a moral person with good values.

There is a strong correlation between age and the share saying it is necessary to believe in God to be a moral person. By 57% to 41%, more of those ages 65 and older say it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values. By contrast, 73% of those ages 18 to 29 say it is notnecessary to believe in God to be a moral person (just 26% say it is).

Those with more education are less likely to say it is necessary to believe in God to be moral than those with less education. Overall, 76% of those with a postgraduate degree say it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be a moral person and have good values, compared with 69% of college graduates, 58% of those with some college experience and just 42% of those with no college experience.

Most black Protestants (71%) and white evangelical Protestants (65%) say it is necessary to believe in God to be a moral person. But the balance of opinion is reversed among white mainline Protestants: By 63% to 34%, they say belief in God is not a necessary part of being a moral person.

Among Catholics, 61% of Hispanics think belief in God is a necessary part of being moral, while 57% of white Catholics do not think this is the case. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated Americans (85%) say it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral.

When it comes to religion’s role in government policy, most Americans think the two should be kept separate from one another. About two-thirds (65%) say religion should be kept separate from government policies, compared with 32% who say government policies should support religious values and beliefs.

A narrow majority of Republicans and Republican leaners (54%) say religion should be kept separate from government policies. However, conservative Republicans are evenly split; 49% say government policies should support religious values and beliefs, while 48% think religion should be kept separate from policy. By roughly two-to-one (67% to 31%), moderate and liberal Republicans say religion should be kept separate from government policy.

Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, 76% think religion should be kept separate from government policies. A wide 86% majority of liberal Democrats say this; a somewhat smaller majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (69%) take this view.

White evangelical Protestants are one group where a narrow majority says government policies should support religion: 54% say this, while 43% say religion should be kept separate from policy. In comparison, majorities of both black Protestants (55%) and white mainline Protestants (70%) think religion should be separate from government policy.

About two-thirds of white Catholics (68%) think religion should be kept separate from government policy; 53% of Hispanic Catholics share this view. Among those who do not affiliate with a religion, 89% think religion and government policy should be kept separate.