Islam is the most common state religion, but many governments give privileges to Christianity

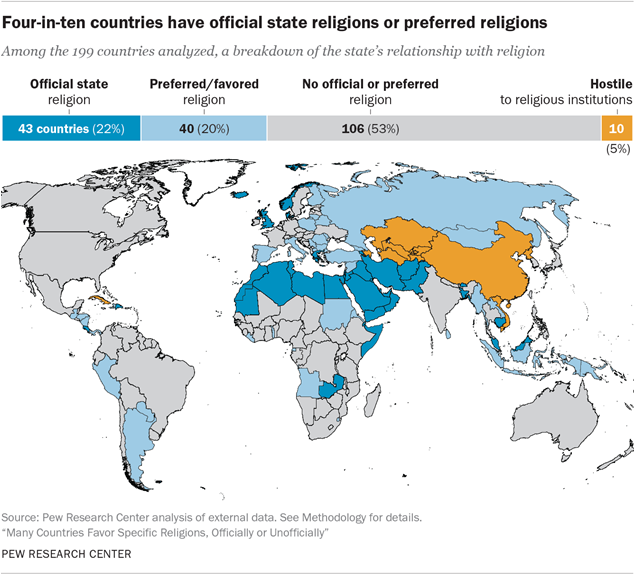

More than 80 countries favor a specific religion, either as an official, government-endorsed religion or by affording one religion preferential treatment over other faiths, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data covering 199 countries and territories around the world.1

Islam is the most common government-endorsed faith, with 27 countries (including most in the Middle East-North Africa region) officially enshrining Islam as their state religion. By comparison, just 13 countries (including nine European nations) designate Christianity or a particular Christian denomination as their state religion.

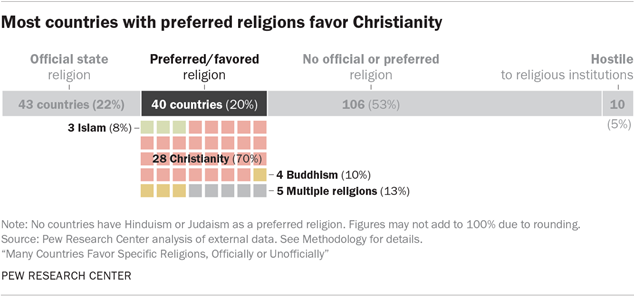

But an additional 40 governments around the globe unofficially favor a particular religion, and in most cases the preferred faith is a branch of Christianity. Indeed, Christian churches receive preferential treatment in more countries – 28 – than any other unofficial but favored faith.

In some cases, state religions have roles that are largely ceremonial. But often the distinction comes with tangible advantages in terms of legal or tax status, ownership of real estate or other property, and access to financial support from the state. In addition, countries with state-endorsed (or “established”) faiths tend to more severely regulate religious practice, including placing restrictions or bans on minority religious groups.

In 10 countries, the state either tightly regulates all religious institutions or is actively hostile to religion in general. These countries include China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam and several former Soviet republics – places where government officials seek to control worship practices, public expressions of religion and political activity by religious groups.

Most governments around the globe, however, are generally neutral toward religion. More than 100 countries and territories included in the study have no official or preferred religion as of 2015. These include countries like the United States that may give benefits or privileges to religious groups, but generally do so without systematically favoring a specific group over others.2

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center analysis of country constitutions and basic laws as well as secondary sources from governmental and nongovernmental organizations. Research on this topic was conducted in tandem with the annual coding process for the Center’s study of global restrictions on religion (for details on this process, see the Methodology section of “Global Restrictions on Religion Rise Modestly in 2015, Reversing Downward Trend”). Coders analyzed each country’s constitution or basic laws, along with its official policies and actions toward religious groups, to classify its church-state relationship into one of four categories:

- States with an official religion confer official status on a particular religion in their constitution or basic law. These states do not necessarily provide benefits to that religious group over others. But, in most cases, they do favor the state religion in some way.

- States with a preferred or favored religion have government policies or actions that clearly favor one (or in some cases, more than one) religion over others, typically with legal, financial or other kinds of practical benefits. These countries may or may not mention the favored religion in their constitution or laws; if they do, it is often as the country’s “traditional” or “historical” religion (but not as the official state religion). Some of these countries also call for freedom of religion in their constitutions – though, in practice, they do not treat all religions equally.

- States with no official or preferred religion seek to avoid giving tangible benefits to one religious group over others (although they may evenhandedly provide benefits to many religious groups). For example, the U.S. government gives tax exemptions to religious organizations under rules that apply equally to all denominations. Many countries in this category have constitutional language calling for freedom of religion, although that language alone is not enough to include a country in this group; coders must determine that these countries do not systematically favor one or more religions over others.

- States with a hostile relationship toward religion exert a very high level of control over religious institutions in their countries or actively take a combative position toward religion in general. Some of these countries may have constitutions that proclaim freedom of religion, or leaders who describe themselves as adherents of a particular religion, such as Islam. Nonetheless, their governments seek to tightly restrict the legal status, funding, clergy and political activity of religious groups.

This research is part of a broader effort to understand restrictions on religion around the world. For the past eight years, Pew Research Center has published annual reportsanalyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The project is jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.

The rest of this report looks in more detail at countries with official state religions or preferred religions, as well as those with no preferred religion and those that are highly restrictive or hostile toward religion. It also explores the implications of these categories.

More than one-in-five countries have an official state religion

As of 2015, fully one-in-five countries around the world (22%) had declared a single state religion, typically enshrined in the constitution or basic law of the country.

In Afghanistan, for example, Islam is the official state religion, stated explicitly in the constitution: “The sacred religion of Islam is the religion of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.”3 The constitution also requires the president and vice president to belong to the state religion – as do some other countries – and other senior officials must swear allegiance to the principles of Islam in their oaths of office. Political parties’ charters must not run contrary to the principles of Islam, and the Ulema Council, a group of influential Islamic scholars, imams and jurists, meets regularly with government officials to advise on legislation.4 The constitution mandates that “No law shall contravene the tenets and provisions of the holy religion of Islam in Afghanistan.”

A slightly smaller share of countries (20%) have a preferred or favored religion. These are not official state religions, but may be listed in the constitution or laws as the country’s traditional, historical or cultural religion(s), and may receive benefits from the state that are not afforded to other religions.

One example of a preferred religion is Buddhism in Laos, where the constitution does not explicitly name Buddhism as an official state religion, but says: “The State respects and protects all lawful activities of Buddhists and of followers of other religions, [and] mobilizes and encourages Buddhist monks and novices as well as the priests of other religions to participate in activities that are beneficial to the country and people.”5 In practice, the government sponsors Buddhist facilities, promotes Buddhism as an element of the country’s identity, and uses Buddhist ceremonies and rituals in state functions. Buddhism also is exempted from some restrictions that apply to other religious groups. For example, the government allows the printing, import and distribution of Buddhist religious material while restricting the publication of religious materials for most other religious groups.6

Elsewhere, a state may favor multiple religions while still providing added benefits to one religion in particular. For example, Russian law designates Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Buddhism as the country’s “traditional” religions, while also recognizing the “special contribution” of Russian Orthodox Christianity to Russian history. The four traditional religions are given certain benefits: Students choosing to take a religious education course may choose between courses on the four traditional religions or a general course on world religions, and a government program funding military chaplains is restricted to chaplains of these four religions. Still, the Russian government shows preferential treatment to the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) in particular. For example, the government provided the ROC patriarch with security guards and access to official vehicles, and an investigation found that major presidential grants given to organizations controlled by or with ties to the ROC were a form of “hidden government support” for the church.7

A slim majority of countries (53%) have no official or preferred religion as of 2015. Within their borders, these countries treat different religions (e.g., Christianity, Islam) more or less equally, and their governments generally have a neutral relationship with religion.

Broadly, the countries in this category can be said to maintain a clear separation of church and state. But it is not necessarily the case that these countries avoid any promotion or restriction of religious practice. France, for instance, has no official or preferred religion, but it did have a “high” level of government restrictions on religion in 2015, according to Pew Research Center’s ongoing research on global religious restrictions. This stems in part from the banning of face coverings in public places, as well as incidents of government harassment of religious groups, including a case where a mayor announced a personally compiled list of “Muslim-sounding” names of schoolchildren in his town.8 (For more details on the correlation between state religions and government restrictions on religion, see below.)

A small share of countries (5%) have no official state religion or preferred religion but nonetheless maintain a highly restrictive or hostile relationship with some or all major religious groups in the country, strictly regulating religious institutions and practices. These are Azerbaijan, China, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, North Korea, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.

China, for example, does not have an official state religion, nor does it have a preferred religion. Nor does it have a preferred or favored religion. Under its one-party political system, however, it has had a heavily restrictive or even hostile state relationship with religion, strictly regulating and monitoring religious institutions. China’s constitution says citizens have “freedom of religious belief,” but it also limits protections to “normal” religious activities.9 In practice, the state closely controls religious activity, and only five state-sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” are allowed to register with the state and hold worship services. The state frequently detained, arrested or harassed members of both registered and unregistered religious groups in 2015.10

Several of the other countries in this category are former Soviet republics: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, religion was tightly restricted by the state and sometimes harshly repressed. Since gaining independence, these predominantly Muslim countries have allowed nominal freedom of worship, and many of their leaders have publicly embraced Islam. Yet their governments have continued to monitor and control religious institutions, including mosques and Muslim clergy.

Islam most common state religion; Christianity most commonly “favored” religion

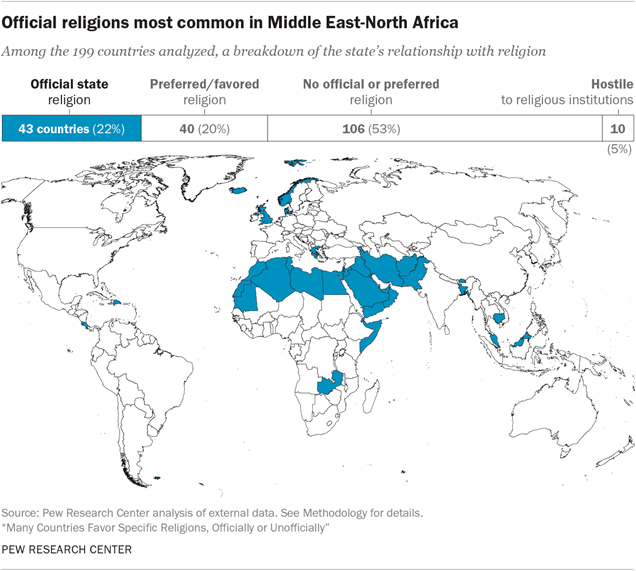

Islam is the world’s most common official religion. Among the 43 countries with a state religion, 27 (63%) name Sunni Islam, Shia Islam or just Islam in general as their official faith.

Most of the countries where Islam is the official religion (16 of 27, or 59%) are in the Middle East and North Africa. In addition, seven officially Islamic countries (26%) are in the Asia-Pacific region, including Bangladesh, Brunei and Malaysia. And there are four countries in sub-Saharan Africa where Islam is the state religion: Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania and Somalia. No countries in Europe or the Americas have Islam as their official religion.

Christianity is the second most common official religion around the world. Thirteen countries (30% of countries with an official religion) declare Christianity, in general, or a particular Christian denomination to be their official state religion. Nine of these countries are in Europe, including the United Kingdom, Denmark, Monaco and Iceland. Two countries in the Americas – Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic – and one in the Asia-Pacific region – Tuvalu – have Christianity as their official state religion. Only one country in sub-Saharan Africa is officially Christian: Zambia.

Buddhism is the official religion in two countries, Bhutan and Cambodia. Israel is the only country in the world with Judaism as its official state religion.11 And no country names Hinduism as its official state religion – though India has a powerful Hindu political party, and Nepal came close to enshrining Hinduism in 2015, when the rejection of a constitutional amendment declaring Hinduism as the state religion led to a confrontation between pro-Hindu protesters and police.12

Among the 40 countries that have a preferred or favored religion – but not an official state religion – most favor Christianity. Twenty-eight countries (70%) have Christianity as the preferred religion, mostly in Europe and the Americas. Five countries in sub-Saharan Africa and three in the Asia-Pacific region have Christianity as the favored religion.

After Christianity, Buddhism is the next most commonly favored religion. All four countries with Buddhism as the favored religion – Burma (Myanmar), Laos, Mongolia and Sri Lanka – are in the Asia-Pacific region. Three countries – Sudan, Syria and Turkey – favor Islam but do not declare it as the state religion.

In some countries, multiple religions are favored to a similar extent by the state. Typically, the government describes these religions as “traditional” or part of the country’s historic culture. It may also provide these groups with legal or financial benefits, such as waiving the requirement to register as a religious group, providing funding or resources for religious education, or providing government subsidies. Five countries – Eritrea, Indonesia, Lithuania, Serbia and Togo – fit these criteria. By contrast, Russia recognizes multiple “traditional” religions, but favors Orthodox Christianity more than the others (see here for more information).

Half of states with official or preferred religions are in the Middle East or Europe

From a regional perspective, the Middle East-North Africa region has the highest share of countries with an official state religion as of 2015. Seventeen of the 20 countries that make up the region have a state religion – and in all of them except Israel, the state religion is Islam. Two others, Sudan and Syria, have a preferred or favored religion (in both cases, also Islam). Lebanon is the only country in the region without an official or favored religion, although key officials are elected or appointed based on religious affiliation (Sunni, Shiite, Maronite Catholic and other minority religious groups) under the terms of Lebanon’s 1943 National Pact, which is intended to distribute power among the country’s major religious sects.

Of the five regions examined in this study, Europe has the highest share of countries (30%) with a preferred or favored religion. All of these countries have Christianity as the favored religion.13 In Georgia, for example, the constitution reads: “The State shall declare absolute freedom of belief and religion. At the same time, the State shall recognize the outstanding role of the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia in the history of Georgia and its independence from the State.”14

In addition to recognition in the constitution, the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC) and the state have a concordat, or constitutional agreement, that governs relations between them. The state does not have a concordat with any other religious group. Through the concordat, the GOC has rights not afforded to other religious groups, including legal immunity for the GOC patriarch and exemption from military service for GOC clergy. And unlike other religious organizations, the GOC is not required to pay a tax on profits from the sale of religious products, value-added taxes on religious imports, or taxes on activities related to the construction, restoration and painting of religious buildings.15

Nine countries in Europe (20%) have an official state religion as of 2015. These include Catholicism in the small states of Liechtenstein, Malta and Monaco; Lutheranism in Denmark, Iceland and Norway; Anglicanism in the United Kingdom; and Orthodox Christianity in Greece and Armenia.16 Altogether, Europe and the Middle East-North Africa region contain 42 countries with either official (26) or preferred (16) religions – together they make up roughly half of all the countries in the world in these categories combined.

Meanwhile, three-quarters of countries in sub-Saharan Africa (75%) have no official or favored state religion, the highest share of any region. Seven sub-Saharan countries (15%) have a favored religion, while five (10%) have an official state religion: Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania, Somalia and Zambia. Zambia is the only one of the five that declares Christianity to be its state religion; the other four are officially Islamic. The constitution of Djibouti, for example, names Islam as “the Religion of the State,” and all other religious groups are required to register with the Ministry of Interior, which requires a lengthy background investigation of each group.17

In the Asia-Pacific region, 10 countries (20%) have an official state religion, and nine countries (18%) have a preferred or favored religion. While 44% of Asia-Pacific countries have no official or favored religion, the region has the highest share of countries (18%) with a hostile relationship with religion. Tajikistan’s constitution, for example, does not recognize a state religion and allows individuals to adhere to any religion.18 In practice, however, the government keeps tight control over religious institutions. It restricts Muslim prayer to certain locations, regulates mosques and bars children (those under 18) from participating in public religious activities. Imams must be approved by the Committee on Religious Affairs, and the content of their sermons is controlled. The government also reportedly has surveillance cameras at mosques, and donations to mosques by individuals are banned.19

One country in the Americas, Cuba, has a heavily restrictive relationship with religion. But roughly seven-in-ten countries in the region (69%) have no official or favored religion. Eight countries in the Americas (23%) have a favored religion, while two – Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic – have Catholicism as the official state religion.

Having an official religion often translates to practical benefits

In a few cases, a country’s official religion is primarily a legacy of its history and now involves few, if any, privileges conferred by the state. And a few other countries fall at the other end of the spectrum, making their official religion mandatory for all citizens.

Much more frequently, however, states with official religions do not make the religion mandatory, but do give it more benefits than other religions, and those states typically regulate other religious groups in the country. More than half (53%) of the 43 countries with official religions meet these criteria. These countries still provide “freedom of religion” on some level – they allow worship by members of other religions, though they give the official religion more benefits or make benefits more readily available to it.

Most of the countries with official religions in the Middle East-North Africa region (59%) have this type of arrangement. In Jordan, for example, Islam is the state religion, and converts from Islam to Christianity were occasionally questioned and scrutinized by security forces in 2015. Non-Muslim religious groups must register to be able to own land and administer rites such as marriage. They are tax exempt, but do not receive subsidies. In contrast, the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs manages Islamic institutions, subsidizes certain mosque-sponsored activities, pays mosque staff salaries and manages clergy training centers.20

In addition, among countries with official religions, three-in-ten (30%) give more benefits to the state religion while also creating an especially harsh environment for other religions (beyond basic regulation of those groups). In these countries, adherence to the official religion is not mandatory, but other religions are not given the same benefits and their activities are sometimes heavily restricted by the government. Most of these countries are in the Asia-Pacific and Middle East-North Africa regions.

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, for instance, all laws and regulations must be based on “Islamic criteria” and the official interpretation of sharia.21 Christians, Zoroastrians and Jews are the only recognized religious minority groups, as well as the only non-Muslim groups allowed to worship as long as they do not proselytize. Public religious expression, persuasion or conversion by these groups is punishable by death. Non-recognized religious groups, like Baha’i, are not free to practice their religion, and even the recognized groups’ activities are closely monitored.22

In a small minority of countries, the official religion is largely ceremonial or it receives some benefits along with its official status. Other religions in the country, however, may be given similar benefits. Among the 43 countries with official state religions, only three – all in Europe – meet these criteria: Liechtenstein, Malta and Monaco.

Monaco, for example, designates Roman Catholicism as the state religion in its constitution: “The Catholic, Apostolic and Roman religion is the religion of the State.”23 Catholic religious instruction is available in schools, but requires parental consent. And while Catholic rituals play a part in some state ceremonies, the law also designates that no one may be compelled to participate in the rites or ceremonies of any religion or to observe its days of rest.24

There also are four states with an official religion – in each case, Islam – that make adhering to that religion mandatory for their citizens: Comoros, Maldives, Mauritania and Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s basic law designates Islam as the official religion, and conversion from Islam is grounds for charges of apostasy – legally punishable by death.25 The basic law requires all citizens to be Muslim, and public worship of non-Muslim faiths is prohibited. While non-Muslims are allowed to worship in private, the government does not always respect this right and has raided such meetings of non-Muslims and detained or deported participants.26

Most states fund activities of official religion

There also usually are financial benefits for official state religions. Among the 43 countries with an official religion, 98% provide funding or resources for educational programs, property or other religious activities.

More than eight-in-ten countries (86%) provide funding or resources specifically for religious education programs or religious schools that disproportionately benefit the official religion. In Comoros, where the official state religion is Islam, the government funds an Islamic studies program, the Faculty of Arabic and Islamic Science, within the country’s only public university.27 Meanwhile, 12% of countries with an official religion provide this type of funding or resources for other religions as well. And only one country with an official religion – Tuvalu – provides no significant funding or resources for religious education programs or religious schools.

In many cases, governments also provide funding or resources for religious property, including for the maintenance, upkeep or repair of religious buildings or land. About half of countries with an official religion (51%) provide funding or resources for religious property that disproportionately benefits the official or preferred religion. In Bahrain, for example, Islam is the official religion, and the government funds all licensed mosques.28

Governments may also provide funding or resources for religious activities unrelated to education or property. These activities include – but are not necessarily limited to – providing media services, supporting worship or religious practices, or paying religious leaders’ wages.

Fully seven-in-ten (70%) countries with an official state religion provide funding or resources for these types of religious activities, primarily for the official religion. For example, in Norway, the Church of Norway was the official state religion and the government provided the salaries, benefits and pension plans of all church employees in 2015.29

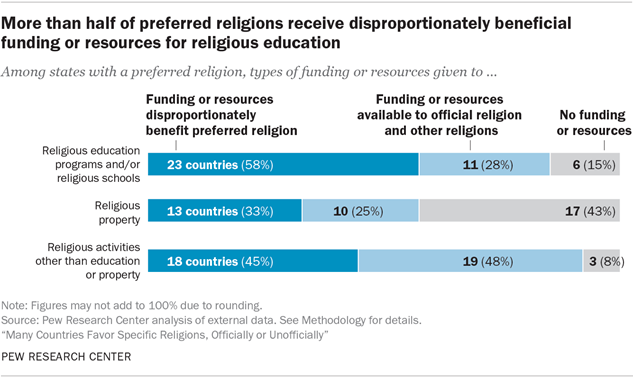

Financial benefits in countries with preferred religions

By definition, all countries with preferred or favored religions (but not official state religions) provide some practical benefits to those religions (see above). But when it comes to one of the most common kinds of benefits – states providing funding or resources to religious groups – there are wide variations in what governments provide and how they provide it.

Over half of countries with preferred religions (58%) provide funds or resources for religious education programs that mostly benefit the preferred religion. For example, in Turkey, where Islam is categorized as a preferred but not official religion, the government has assigned tens of thousands of students to state-run religious schools known as “imam hatip” schools, while limiting the number of students who can be admitted to public secondary schools. From 2003 to 2015, the number of students in the imam hatip schools rose from 63,000 to about 1 million, and some secular parents have voiced concern that this amounts to heavy-handed government support of religion through education.30

About a third of countries with preferred religions (28%) provide state funding or resources for religious education programs not only for the favored religion but also for other religious groups. And 15% do not provide significant funding or resources for any religious education programs.

Fully one-third of countries with favored religions (33%) provide funding or resources for religious buildings or property in a way that disproportionately benefits the favored religion. In Burma (Myanmar), for example, Buddhism is the unofficial, favored religion, and non-Buddhist religious groups reported difficulty repairing religious buildings and building new facilities.31 At the same time, a quarter of countries (25%) with a preferred religion also provide funding or resources for building or maintaining property belonging to other religious groups as well. Guatemala is one of these countries; the government provides tax exemptions for properties of all registered religious groups, while Catholicism is favored by the government in other ways.32

Most countries with a preferred or favored religion also provide funding or resources for religious activities unrelated to education or property, with 45% providing support predominantly for the favored religion and 48% providing support for other groups as well. In Liberia, for instance, the government has provided tax exemptions and duty-free privileges to registered organizations, including missionary programs, religious charities and religious groups. This benefit was offered to all registered groups, and was not limited to Christians, the favored religion in Liberia.33

Central and Eastern Europeans in countries with official or preferred religions are more likely to support church-state links

In Central and Eastern Europe, the relationship between church and state in a country is often reflected in public opinion on the topic. For example, people in countries with official or preferred religions are more likely to support government promotion of religious values and beliefs, as well as government funding of the dominant church; they also tend to believe religion is important to their sense of national belonging.

Pew Research Center’s recent survey of 18 countries in Central and Eastern Europe – covering most, but not all, of the region – included 11 countries with official or preferred religions (usually Orthodox Christianity) and seven with no official or preferred faiths.34

Pew Research Center’s recent survey of 18 countries in Central and Eastern Europe – covering most, but not all, of the region – included 11 countries with official or preferred religions (usually Orthodox Christianity) and seven with no official or preferred faiths.34

Respondents in all 18 countries were asked whether they think their government should promote religious values and beliefs, or if religion should be kept separate from government policies. On balance, people in Central and Eastern European countries with no official or preferred religion are more likely to say religion should be kept separate from government policies (median of 68%) than are those who live in countries with an official or preferred religion (median of 50%).

Among countries with official or preferred religions, Poland is an exception to this pattern, because of its strong support for separation of church and state (70%). Relations between the Catholic Church and Polish government are enshrined in a concordat that, among other things, grants the Catholic Church unique privileges in church-state discussions. Polish adults appear to recognize this level of influence – three-quarters (75%) say religious leaders have at least some influence in political matters. Many Poles, however, are uncomfortable with it; a majority (65%) believe religious leaders should not have this much political influence.

Among countries with official or preferred religions, Poland is an exception to this pattern, because of its strong support for separation of church and state (70%). Relations between the Catholic Church and Polish government are enshrined in a concordat that, among other things, grants the Catholic Church unique privileges in church-state discussions. Polish adults appear to recognize this level of influence – three-quarters (75%) say religious leaders have at least some influence in political matters. Many Poles, however, are uncomfortable with it; a majority (65%) believe religious leaders should not have this much political influence.

Another survey question asked Central and Eastern Europeans about their attitudes toward government funding of churches. Across countries with an official or preferred religion, more people support governments giving financial support to the dominant church in the country (median of 53%) than in countries without an official or preferred religion (median of 39%).35 For example, in Armenia, a majority of respondents (62%) say the government should fund the Orthodox Church (the official state religion).

But two countries stand out: Greece and Poland. In Greece, where Orthodoxy is the official state religion, just 18% of people think the government should give financial support to the Orthodox Church. And in Poland, only a minority (28%) say the Catholic Church should receive financial support from the government.

Still, for many Central and Eastern Europeans – including Greeks and Poles – religion plays an important role in their sense of national belonging. Across the region, a median of 59% say being a member of the dominant denomination in the country is “very” or “somewhat” important in order to truly share their national identity – for example, to be “truly Greek” or “truly Polish.”

Again, these attitudes vary considerably when comparing countries that have an official or preferred religion with countries that do not have this type of church-state relationship. Across the surveyed countries with an official or preferred religion, a median of 66% say being a member of the dominant faith (e.g., Orthodoxy in Greece, Catholicism in Poland) is very or somewhat important to truly belong to the nationality. In countries without an official or preferred religion, fewer people (a median of 43%) feel this way.

Again, these attitudes vary considerably when comparing countries that have an official or preferred religion with countries that do not have this type of church-state relationship. Across the surveyed countries with an official or preferred religion, a median of 66% say being a member of the dominant faith (e.g., Orthodoxy in Greece, Catholicism in Poland) is very or somewhat important to truly belong to the nationality. In countries without an official or preferred religion, fewer people (a median of 43%) feel this way.

Members of the official or preferred faith also are much more likely than members of other religions to think the dominant faith is an important element in national belonging. Across countries with an official or preferred religion, a median of 81% of members of the dominant faith say being a member of that faith is very or somewhat important for national identity. In contrast, only about a third (median of 31%) of people in those countries who are not members of the dominant faith think it is very or somewhat important.36

On some other issues, publics in Eastern Europe have similar views regardless of their country’s church-state relationship. There is no clear difference, for example, on views about democracy. In countries with or without official or preferred religions, similar shares of people view democracy as preferable to any other kind of government (medians of 47% and 46%, respectively). Similarly, on the topic of pluralism, medians of 50% in both types of countries say it is better if society consists of people from different nationalities, religions and cultures (as opposed to a homogeneous society).

Government restrictions higher in countries with official or preferred religions

In some ways, states that have an official or preferred religion tend to behave differently from states that do not. Not only are they more likely to provide financial or legal benefits to a single religion, but they also are more likely to place a high level of government restrictions on other religious groups.

These restrictions are analyzed using the Government Restrictions Index (GRI), a 10-point scale measuring government laws, practices and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices, with a score of 10 indicating the highest level of restrictions.37 In countries with an official state religion, the median GRI score was 4.8 in 2015, compared with 2.8 in countries with preferred or favored religions and 1.8 in countries with no official or preferred religion.38

This relationship holds true even when controlling for the countries’ population size, level of democracy and levels of social hostilities involving religion (because government restrictions may be a response to social hostilities).39 Taking all of these factors into account, states with an official religion still score, on average, 1.8 points higher on the Government Restrictions Index than states with no official or preferred religion.

One of the ways states with official or preferred religions restrict religion is through formally banning certain religious groups.40 Among the 34 countries in the world that have this kind of ban in place, 44% are countries with an official state religion, while 24% are countries that have a preferred or favored religion. Banning of religious groups is much less common among states that do not have an official or preferred religion, with only three countries in this category – the Bahamas, Jamaica and Singapore – maintaining formal bans on particular groups in 2015.41

Again, this relationship holds even when taking population size, democratic processes and social hostilities into account. In other words, countries with an official or preferred religion are more likely to enact bans on some religious groups than countries without an official or preferred religion – regardless of how large a country is, how democratic it is or how widespread social hostilities involving religion are within its borders.

In Malaysia, for example, Islam is the official religion, and a 1996 fatwa required the country to follow Sunni Islam teachings in particular. Other Muslim sects, like Shiite, Ahmadiyya and Al-Arqam Muslims, are banned as deviant sects of Islam.42 These groups are not allowed to assemble, worship or speak freely about their faith.

States with official or preferred religions also are more likely than other states to interfere with worship or other religious practices. Among these countries, 78% interfered with the worship of religious groups in 2015 to some degree (e.g., in a few cases, many cases or a blanket prohibition). By comparison, 46% of countries with neither an official or preferred religion interfered with worship practices.43

For example, in Peru – where Catholicism is the preferred religion – Protestant soldiers reported that the military’s lack of Protestant chaplains made finding Protestant church services difficult. Meanwhile, Muslims and Jews in Peru complained that non-Catholic religious holidays were not provided to students or employees.44

- This analysis includes the 198 countries and territories typically studied in Pew Research Center’s annual reports on global restrictions on religion, plus North Korea. Although North Korea is not included in the annual reports because of the difficulty of obtaining reliable, up-to-date information on events inside its borders, information on its overall policy toward religion is readily available. For more detail on why North Korea often has been excluded from other analyses, see the Methodology section of Pew Research Center’s April 2017 report, “Global Restrictions on Religion Rise Modestly in 2015, Reversing Downward Trend.” ↩

- While these countries may not legally recognize a religion as the state religion or give benefits to one group over others, they may restrict religion in other ways. To examine these actions, Pew Research Center conducts a separate, broader, analysis of government restrictions on religion each year. For the latest report, see “Global Restrictions on Religion Rise Modestly in 2015, Reversing Downward Trend.” ↩

- Constitute. 2004. “Afghanistan.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Afghanistan.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Constitute. 2003. “Lao People’s Democratic Republic.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Laos.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Russia.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “France.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Constitute. 2004. “China.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau).” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Israel’s basic law defines the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” Although “Jewish” could be interpreted in this context as referring to religion, ethnicity or both, Israel is coded as having an official religion in part because the Israeli government gives legal authority to the chief rabbinate and provides special benefits to Judaism, such as support for religious study. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Nepal.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Two of these countries – Lithuania and Serbia – also include Judaism and Islam as “traditional” or favored religions. ↩

- Constitute. 2013. “Georgia.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Georgia.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- A constitutional amendment in 2012 began the process of separating the Church of Norway from the state, although the provisions of the amendment did not formally take effect until Jan. 1, 2017. The amended constitution refers to the church as the “Established Church of Norway” and continues to stipulate that the king must be of the Evangelical-Lutheran faith. The state continued to provide financial support for the church and paid the salaries of church staff until Jan. 1, 2017. The data in this report are based on state religions in 2015, and therefore include the Church of Norway as an official state religion. See Hofverberg, Elin. Feb. 3, 2017. “Norway: State and Church Separate After 500 Years.” The Law Library of Congress. ↩

- Constitute. 2010. “Djibouti.” Also see U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Djibouti.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Constitute. 2003. “Tajikistan.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Tajikistan.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Jordan.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Constitute. 1989. “Iran (Islamic Republic of).” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Iran.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Constitute. 2002. “Monaco.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Monaco.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Constitute. 2013. “Saudi Arabia.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Saudi Arabia.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Comoros.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Bahrain.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Norway.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Turkey.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Burma.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Guatemala.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Liberia.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Among these countries, Lithuania and Serbia both have multiple preferred religions, including various Christian denominations. ↩

- In Bosnia, respondents were asked about public funding for regional churches; results are not analyzed here because the question was not directly comparable to what was asked in other countries. ↩

- Lithuania and Serbia have multiple preferred faiths, however, the dominant faiths in these countries are Catholicism and Orthodoxy, respectively. ↩

- The Government Restrictions Index is typically comprised of 20 indicators. One of these indicators focuses on whether the government favors a specific religion, including whether it gives funds or other benefits to the religion. Since this is highly correlated with whether the state has an official or favored religion, the index was recalculated without this indicator for the purposes of this analysis. The scores for the remaining 19 items were added and divided by 1.9 to result in a new overall GRI score between 0 and 10, with 10 indicating the highest level of government restriction on religion. ↩

- This analysis does not include the last category of state-religion relationships: states with no official or preferred religion that are hostile toward religious institutions. This is because the elements that help classify a country in this category are based on elements in the GRI. In other words, states with these state-religion relationships will, by definition, always score highly on the GRI; it is an endogenous relationship. At the same time, other countries may have an official or preferred religion for reasons completely separate from the GRI indicators. ↩

- Data for population sizes in 2015 from UN population estimates. See United Nations Population Division. June 17, 2013. “World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision.” UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Data on democracy levels come from the Polity IV Project; see The Polity Project. “About Polity.” Center for Systemic Peace. Data for social hostilities come from original Pew Research Center analyses. ↩

- This includes banning a group for non-security reasons, or banning a group for both security and non-security reasons. It does not include banning only for security reasons (even though there may be some situations where states use security reasons as justification for banning a group when there may be other motives, including religious or political ones). ↩

- Jamaica maintains a ban on Obeah, an Afro-Caribbean shamanistic religion, although it is not actively enforced. ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Malaysia.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩

- Again, this analysis does not include countries with no official or preferred religion that are hostile to religious groups, since interference with the worship of religious groups factors into the classification of these countries as “hostile.” ↩

- U.S. Department of State. Aug. 10, 2016. “Peru.” International Religious Freedom Report for 2015. ↩